I was fortunate enough to visit the exhibition entitled ‘Dürer’s Journeys – Travels of a Renaissance Artist’ at the National Gallery in London recently. Deservedly very popular, it chronicles the travels of Albrecht Dürer though renaissance Austria, Italy and the Netherlands. He met a series of artists and other inspiring people which sparked a series of artistic masterpieces – both paintings and engravings, including his famous ‘Madonna and Child’. His observational powers were remarkable, and it was clearly the people that interested him most. It all added up to a powerful insight into the fast-changing time of the renaissance.

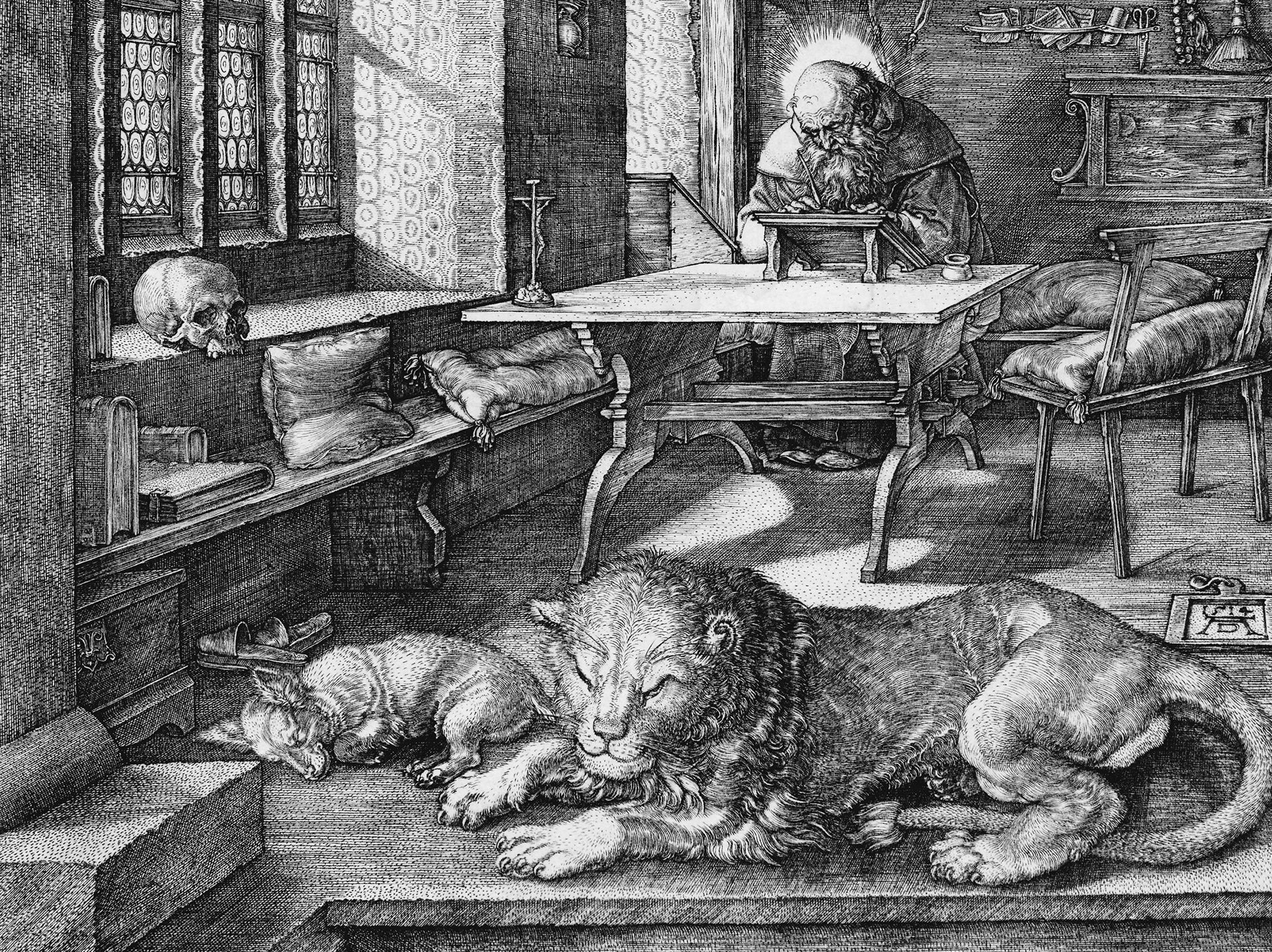

But the work that really struck a chord with me as a linguist was copper engraving ‘St. Jerome in this study’ from 1521, shown below – and I had already seen a similar work by Antonello da Messina earlier in the main gallery amongst other works on the same topic such as Giovanni Bellini’s ‘St Jerome reading in a landscape.’ Dürer’s image is of St Jerome engrossed in his work of translating the bible into Latin from Greek and Hebrew. Dürer, a polymath also known as a writer and theoretician, was also a supporter of Martin Luther, translator of the bible from Latin into vernacular German.

Image taken from Wikipedia.

St. Jerome lived from 347 A.D. to 420 A.D., and his bible became the predominant text used by the Roman Catholic Church. Its importance was clearly valued and respected by renaissance artists and their audience. Through Luther’s work, the rapid translation and distribution of the bible during the Protestant Reformation, Christianity had two clear paths – Roman Catholicism or Protestantism. Translation was right at the heart of the renaissance and the reformation, increasing transparency and enabling Luther and others to question the practices of the powerful Catholic church.

The next question for a linguist is more practical though – how many languages did this polymath Dürer speak, and how was he able to converse with the people that he met on his travels? His father was originally Hungarian, but Albrecht was born and raised in Nuremberg – so he spoke German, and indeed wrote his famous books on human proportions in German (Vier Bücher von Menschlicher Proprtortion.) Did he speak Italian (or an Italian dialect) when in Italy or Dutch in the Netherlands? Latin was the most important language in Europe during the renaissance. Throughout the Middle Ages, Latin had been essential to learning, religion, and government. So maybe in some situations he used Latin as a Lingua Franca in the way that English can be used around the world today – and no doubt he used interpreters, whether formally or informally for the spoken word. Maybe he commissioned translators for the written word when communicating with other great artists such as Raphael? Of course, I would love to know if anyone has read any insights!

Highly skilled translators and interpreters are just as essential in today’s world for facilitating communications across languages and cultures – whether for business purposes, government or indeed art and literature. This year, I shall be keener than ever to join linguists the world over in observing International Translation Day on 30th September – the Feast Day of St. Jerome, the patron saint of translators. The Dürer exhibition runs until 27th February.

To discuss your translation needs and requirements, drop us a message today or reach us over the phone on 01943 839227 (+44 1943 839 227 outside of the UK).

Mark with Jo Robinson

January 2022